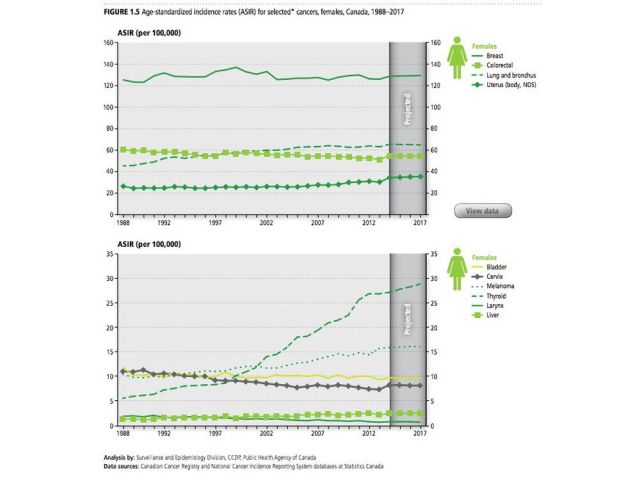

Adjusted for age, the overall incidence rate of all cancers for all Canadians is in decline, but when you focus on women alone, the incidence is still creeping upward, according to a 2017 report by the Canadian Cancer Society. For men, the “all cancers” rate is in steady decline.

Those numbers encompass upward and downward trends for dozens of different cancers — melanoma is trending up for both sexes, prostate and cervical cancers are dropping.

Lung cancer diagnoses explain most of the difference, said John Spinelli, vice-president of population oncology at the B.C. Cancer Agency.

Men picked up smoking very quickly during the 1950s and ’60s and they are still diagnosed with cancer more often than women, largely because the disease takes decades to develop.

“When smoking started to decline, it came much earlier for men than women,” he said.

Even worse, while men were starting to quit smoking in large numbers in the 1970s, women were still picking up the habit. Women in B.C. were quitting in droves by the late 1990s, according to the report Tobacco Use in Canada, but the lag time for improving cancer rates is 20 years or more.

“So, we haven’t yet seen the decline we would expect from women quitting, and that is true across western cultures,” he said. “We are hoping to see those rates start to drop soon.”

Since peaking in 1988, death due to cancer has been falling steadily for both sexes, according to Statistics Canada data. The Canadian Cancer Society estimates about 180,000 deaths — especially from lung and breast cancer — have been avoided as a result of improved treatment and surveillance programs, such as breast cancer screening.

Mortality due to prostate cancer in men has been in decline as a result of improved treatment, Spinelli said. Prevention may be a pipe dream, as age appears to be the main driver.

“We really don’t know what the causes are, but not long ago the thinking was that if a man lives long enough, he will get prostate cancer,” he said, noting that even in men who die of other causes, biopsies show about one-third also have prostate cancer.

Only one card to play

In a 2014 U.S. Surgeon General’s report on smoking, the bottom line is that quitting at the time of diagnosis can lower your risk of death by up to 40 per cent, better than all existing cancer therapies.

“Just stopping smoking and nothing else was your best treatment for cancer,” said Dr. Renelle Myers, a lung health specialist at Vancouver Coastal Health.

Myers is working with Spinelli to establish a smoking cessation program in Vancouver at the B.C. Cancer Agency.

“It’s really just a part of your cancer treatment,” she said. “There’s a perception among people and even health care providers that once you have cancer, it’s too late. Why put yourself through it?”

The truth is that quitting reduces your chances of death generally, and specifically from cancers that you may not think of as smoking-related, such as prostate cancer and breast cancer.

Smoking is also known to interfere with cancer treatments, including radiation and targeted chemotherapy.

“Individual studies out there that show if you are undergoing radiation therapy to treat your cancer you have a 20-per-cent greater chance of complications if you continue to smoke,” she said. “We think that it has to do with a lack of oxygen in the tissues.”

Studies have also found that patients who smoke during chemotherapy need far more medicine to be effective, which is not accounted for during treatment.

“That’s not how we dose the drugs,” she said.

When people get a cancer diagnosis, their instinct is to look for every advantage, anything that will help you survive. Many turn to kombucha, a fermented colony of bacteria and yeasts. Others gulp down green tea or green juice. Almost anything green has to be good, right?

“What they should do is eat well and quit smoking,” said Myers. “And we want to make smoking cessation a seamless part of cancer treatment of your cancer journey.”

The program will combine nicotine replacement systems or medications that affect nicotine receptors with long-term counselling.

“The key is followup,” she said. “You can’t just see someone once and then, see ya.”

A light went on

Lung and colon cancer survivor John Johnston smoked for 54 years before his diagnosis. Although he had no symptoms, based on his age and smoking history, his new family doctor ordered a CT scan, which revealed two lesions in his lung and “a wide range of polyps” in his colon.

“I was very lucky,” he said. “Without that scan I would have been much farther down the path before they were discovered, but everything was caught early.”

He was counselled to quit smoking by his health care team at the time, but didn’t. At least not yet.

Johnston, 69, was in the hospital for three days after his lung collapsed during a biopsy on his tumour, the first time he had been in an environment where smoking was simply not an option. He noticed something unexpected.

“I found that I didn’t miss smoking. It didn’t really bother me,” he said.

He resumed smoking when he was released, because, as he put it: “My wife and I both smoke, so it was something we were going to have to do together.”

A few days and a couple more smokes after his lung cancer surgery, he met with a respirologist who explained that his lungs — already at less than 40 per cent capacity — would continue to decline quickly if he continued to smoke.

“She was clear and factual and explained that I would be on oxygen within six to 12 months, and downhill from there,” he said. “It’s like a light went on and I thought, ‘You’ve got to stop this.’ I haven’t had a cigarette since that meeting.”

In the three months since quitting, he has recovered some lung power and climbs stairs with ease again.

“I am very lucky, everything has gone well,” he said. “After stopping, I’m feeling way better.”

Quitting smoking is one way that patients can regain some of the loss of control that accompanies a lung cancer diagnosis, said Dr. Christian Finley, Johnston’s surgeon.

“No one wants to meet me,” he said. “It’s a really stressful moment and they are really looking for some way to help themselves, so I can help them get focused on something that reduces their chances of getting another cancer or other disease.”

What ultimately spurs a patient to quit is highly individual, said Finley, a surgeon at St. Joseph’s Health Centre in Hamilton. For some, the diagnosis is enough, and for others nothing will ever be enough.

“It’s a bad addiction, and that so many people smoke when we know how bad it is speaks to that,” he said. “I’ve had patients who want to go outside for a smoke after I’ve taken out their lung.”

For those patients, the days of recovery in hospital after surgery presents an opportunity to work through the worst of their withdrawal symptoms so they can quit for good, he said.

We are a little bit different

“Generally, we see higher disease rates in (Eastern Canada) than we do in the West,” said Spinelli. “British Columbia has among the lowest cancer incidence rates in Canada, and the lowest for most major types of cancer.”

British Columbians are less likely to be smokers than other Canadians — about 10.2 per cent smoke compared to the national average of 13 per cent, according to a report by University of Waterloo researchers. That is down by half since 1999. Smoking is associated with lung, esophageal and even bladder cancer.

Differences in diet and access to the outdoors compared to other provinces are thought to be factors that favourably influence cancer rates in B.C., but our ethnic mix may play a role, too.

Women in Asia have much lower rates of breast cancer than in Canada — likely a result of differences in lifestyle and possibly genetic factors — and when they immigrate they retain some benefit, said Spinelli.

Immigration may also be driving the increasing incidence of liver cancer related to exposure to hepatitis B, which is prevalent in Asian countries.

Cancer rate outliers

A massive increase in diagnosis of thyroid cancer — especially in women — may strangely enough be a good news story. It’s not a terribly common cancer and the change in incidence is probably not related to changes in lifestyle or even our environment, said Spinelli.

“We are diagnosing smaller and smaller thyroid tumours,” he said. “What we think is that we have just gotten much, much better at finding it, especially because we don’t see mortality rates increasing.”

The incidence of melanoma in Canadian men is up roughly 100 per cent in the past 30 years and about 50 per cent in women.

“Melanoma is among the fastest-growing cancers in males and females and we have a good idea that it’s related to people’s sun exposure in childhood, but the latency period is incredibly long,” he said. “(The increase) is probably related to people getting sunburns as much as 40 years ago.”

On the upside, the message on sun safety seems to be sinking in, as melanoma rates for young British Columbians are not increasing.

Age matters

Cancer risk increases very strongly with age. Canada’s average age is rising and our population is growing and that means that ever-more people are going to be diagnosed with some form of cancer. But that rising number obscures the progress being made in prevention and treatment.

The irony is that by living longer and treating cancer more successfully, the raw incidence of cancer and mortality due to cancer are rising, as every added year of life provides more opportunity for new cancers to develop.

“It’s a strange paradox that living longer puts you at a higher risk of cancer, but it puts you at risk of many other diseases as well,” said Spinelli.

source:-vancouversun.