When Simon Cox was first diagnosed with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) 13 years ago, he feared the worst. But now there are promising developments in the search for a cure. He meets patients taking part in a new trial.

Being told I had cancer wasn’t the scary part. The compassionate female doctor explained that I had Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL). It is the most common form of leukaemia and in many patients it does not cause problems for decades, if at all.

Like most patients, I had no symptoms and I was diagnosed out of the blue, after a routine blood test. I would have to wait for a year to see whether the CLL was going to need treatment. The doctor said if I did, it would involve chemotherapy or bone marrow transplants.

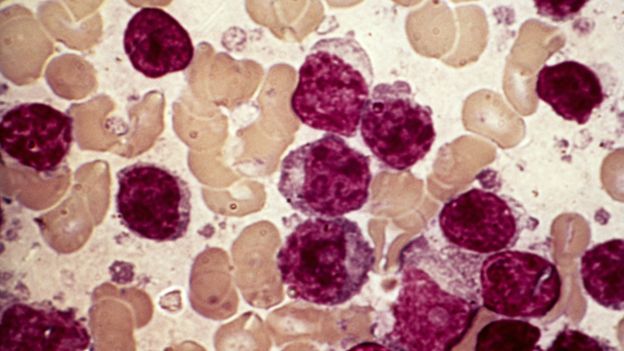

CLL is a disease of the immune system. Lymphocytes are cells that fight infections and then die off, but with CLL they grow out of control and can’t be switched off.

The kicker came a month later when I saw my hospital consultant. The room was bare and functional with flat light coming in from a small window. The consultant sat behind a desk as he looked through my first set of blood tests. He asked if I was planning to have more children. When I said “Yes”, he said I might need to re-think that – because I might not be around to see them grow up.

I mentioned the treatment options such as bone marrow transplants. He said there was a high probability of the transplant failing, and that my internal organs would collapse. He made it clear to me that CLL was incurable.

I was 37, with a wife and young daughter and thought I would die before I was 40. I clung to my wife’s hand and began to cry. The doctor responded by dictating a letter repeating the grim prognosis he had just told me. I later found out his gloomy predictions had earned him the nickname “Dr Death”.

Luckily for me he was wrong. Thirteen years on, I have two daughters and I haven’t needed any treatment – my prognosis is very good. But that’s not the case for many patients.

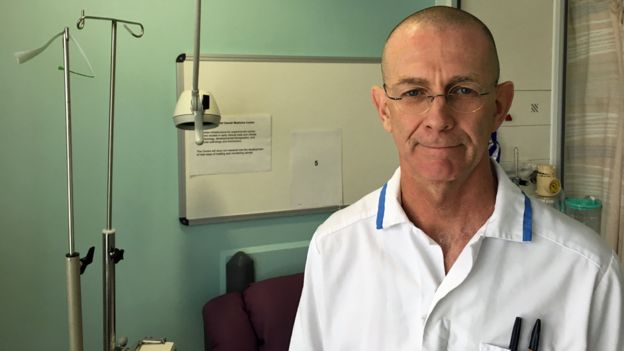

At my annual check-up my subsequent consultant, Prof Amit Nathwani, told me about the amazing developments in CLL treatment and a possible cure. This led me at the start of 2017 to St James’s Hospital in Leeds, to meet Peter Hillmen, Professor of Experimental haematology. Tall and rangy, with flecks of grey in his dark hair, Prof Hillmen is on a mission to find a cure for my type of cancer. In his warm Yorkshire accent, he told me about a trial he was conducting that could be the breakthrough.

When Prof Hillmen first became a consultant haematologist two decades ago there was only one chemotherapy treatment available, which had been around since the 1950s. If it failed, there was little hope he could offer.

“I’ve sat in front of patients for over 20 years who I know are going to die of CLL, and as a doctor that’s really hard,” he says. He hopes his new trial will mean having far fewer of these conversations.

Find out more

- Listen to Find me a cure on 6 February at 11:00 on BBC Radio 4

- Or catch up via the iPlayer

Clarity is a trial of 50 CLL patients from across the UK who have had chemotherapy but whose disease has returned. Sponsored by the charity Bloodwise, it is the first CLL trial in the world to combine two non-chemotherapy drugs – Venetoclax and Ibrutinib. They target two separate elements of the disease – the proliferation of cells and the inability of cells to die off when they are no longer needed. This form of targeted treatment is seen as the way forward for treating all cancers.

Image copyrightSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Image copyrightSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYAndy Wright was one of the first patients to be recruited onto the trial in the summer of 2016. Before joining, he was extremely ill.

“I started to lose my hearing, I had massively high temperatures, night sweats and my glands in my neck got as big as my head,” he says. “It was very scary. I started thinking, ‘Am I on my way out?'”

When he was first diagnosed eight years ago, Andy was stocky and fit, cycling up hills to his job packing power tools. He went through a course of chemotherapy, but in 2016 the cancer returned. For patients in this position the average survival is a few years.

Weeks after starting treatment, the swelling in Andy’s glands had gone and he was starting to feel like his old self. He was the first patient I had met who has the same disease as me.

He was fascinated by my lack of symptoms. I saw how differently it could have turned out for me and felt a bit guilty at my lack of problems – almost a fraud. I could empathise with the strain it had placed on his family.

For Andy’s wife Tracey, his diagnosis was a troubling time, especially as they have four young children to look after. We talked in the garden of their neat little semi in Wakefield, out of earshot of the children.

“It was a shock, you just think of death straight away,” she says. “It’s the not knowing that’s the scary part – how long until it begins to affect him, and when it’s going to happen, you just don’t know.”

By early 2017 Prof Hillmen could see from the patients’ regular blood tests that the treatment was safe. It also seemed to be working, but a more accurate measure would be the bone marrow tests taken after six months.

In the spring of 2017 Richard Oates let me sit in on his test. He has had CLL for almost as long as me. He was in his mid-40s when he was diagnosed, and retired early from the furniture business that his family had run for generations. After having chemotherapy he went into remission, and when the CLL returned he was put forward for the Clarity trial.

Richard remembers how he felt when he was told he had cancer and might die within a few years.

“It frightens you to death,” he says. “I probably went into denial.” Now he is more philosophical about his illness. “If your time’s up, then your time’s up. I’m quite laid-back about stuff like that.”

When I had my bone marrow test I was put to sleep. Richard was wide awake and winced as the nurse inserted the long needle into his thigh to extract a tiny nugget of marrow to be tested in the lab at the end of the corridor. Prof Hillmen was hopeful he would see a steep fall in the cancer cells in the bone marrow. For most patients who start treatment, 95% of their bone marrow cells have CLL.

“If we see marked reductions that would be encouraging,” he says.

Richard no longer bothered getting his wife Debbie to come to appointments with him. She would stay at home in their old stone house looking out over the Pennines where they walk their dogs each day. Debbie was spooked by the possible side effects of the trial, such as severe sickness or even death. The treatment also meant their chance of having children was at an end.

“They recommend you don’t even try,” she says. “At my age we were getting to the point where it was now or never, and that made it never. That was quite hard.”

Andy Wright was one of the first patients to have his bone marrow taken and in the late spring of 2017 he returned to St James’s Hospital to get his results. When his treatment began, 84% of his bone marrow cells had CLL. After eight months on the trial that had come down to 0.0085, a 10,000% reduction.

Although the disease had not gone entirely, and could potentially return, Andy was understandably pleased.

“It’s fantastic,” he says. “A top, top result.” Time to celebrate. “I might say to my wife, ‘Let’s have a Chinese’ and have myself a tin of cider.”

Across the Pennines, Richard Oates had also responded well to the trial. When I met him again in the autumn he had a tiny percentage of CLL cells in his bone marrow, but he was still phlegmatic about the results.

“I said to the doctor: ‘That’s quite good.’ He said: ‘It’s excellent!’ I’m a Yorkshireman, I don’t get carried away too much,” Richard says.

The trial team hope to get rid of the disease totally from his system. “Presumably then they will stop giving me the treatment.”

For Andy and Richard the signs were encouraging but the big test for the trial came in December 2017 in Atlanta in the US. Prof Hillmen presented the results from the first six months of the trial to the American Society of Haematologists, a huge conference of 30,000 blood cancer specialists from around the world.

The data showed all of the patients in the trial had responded to treatment, and that after six months a third had no CLL cells in their system. These results exceeded what the team had hoped to achieve in a year. Other leading haematologists described the results as “remarkable” and a “paradigm shift” in treatment. Prof Hillmen said the unprecedented response meant a cure was now much closer.

“It really suggests we are going to see a huge change in the next few years,” he says.

Clarity is a phase two trial where all patients are given the new drugs. Its success means it is being incorporated into a much larger phase three trial where it will be compared to the current gold standard, chemotherapy. This is what’s known as “adaptive trial design” which Dame Tessa Jowell movingly spoke about in the House of Lords last month. Rather than start from scratch, when new drugs come along they are incorporated into existing trials. The aim is to get treatments to patients sooner.

We will only know if this is a cure in five or 10 years. From a personal point of view I want it to succeed, as one day I may need it. For Andy Wright it has been a lifesaver.

“I’m still alive, still here. If it wouldn’t have been for the treatment, I don’t think I would be alive today.”

source:-BBc