In general, we know that exercise improves heart health. But researchers at the University of Guleph have also used it as a tool to uncover a handful genes that might lead to heart disease down the line, particularly for men.

If your body increases blood pressure in response to exercise by an amount that’s higher than normal, then it could be a sign of later issues, according to a new study.

It’s important to remember that everyone’s body reacts differently to exercise, but all of us experience spikes in blood pressure in heart rate. This new studypublished this week in The Journal of Physiology, the illustrates that for a handful of people with a specific set of genetic mutations, that blood pressure response might be slightly higher than you might expect.

The study’s lead author Philip Millar, Ph.D, an associate professor at the University of Guelph, tells Inverse that this elevation may act as an early warning sign of potential issues with high blood pressure to come:

“We know that exaggerated blood pressure responses to exercise are a risk factor for future cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” Millar tells Inverse. “So we are understanding or trying to predict who is going to exhibit these responses.”

The Exercise Pressor Reflex

Millar had 200 participants perform a “static hand grip exercise” during which he measured blood pressure, and also ran a series of genetic tests. His analysis showed that those with the higher blood pressure during exercise had tiny, genetic differences that resulted in higher blood pressures during their admittedly lame workout task. But to identify why these genetic changes affect blood pressure, Millar decided to tune into the elegant way that the body talks to itself during exercise, called the exercise pressor reflex.

When you start to run, jump, or perform any workout a few things happen in your muscles, and nerves that tell your brain how much blood they’ll need to help you perform your chosen activity. Firstly, the actual movement and compression of muscle plays a role:

“Stretch and compression of the muscle is picked up by nerve endings, and they send messages back to the brain stem to help regulate pressure to drive blood flow during exercise,” Millar says.

But that’s just one way the brain and muscles communicate. The brain is also adept at receiving messages from a series of receptors all over the body that pick up on “metabolites” or by-products of energy burning and tell the brain to kick the heart into action that way. After receiving messages through these two pathways the brain can then respond: restricting blood vessels to increase blood flow, or increasing heart rate.

“Our study was focused mainly on the metabolic component,” he says. “We wanted to see the potential differences in the receptors that pick up on these metabolites and how might impact the blood pressure response.”

A Potential Warning Sign

It turned out that surprised that some of his participants had tiny differences in the genes that code for two particular receptors found in muscles, called TRPV1 and BDKRB2. These are two metabolite receptors that play a role in sending messages during the exercise pressor reflex that eventually end up in the brain stem — telling the body to increase or decrease heart rate or blood pressure.

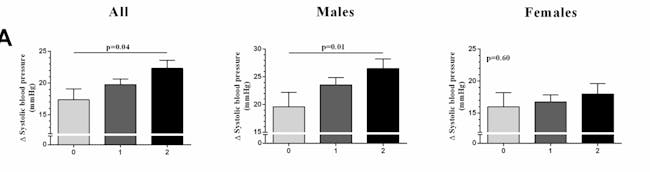

In general, those with one particular variant had between a 22 and 23 percent greater differences in blood pressure than those without it. But the differences were more pronounced in men: when with one specific geneotype tended to have slightly higher blood pressure readings than their female counterparts with the same gene. For now, Millar isn’t sure why this is, and it will likely need further investigation.

Even more notably, when Millar had these participants perform another “mental stress task” he didn’t see these spikes in blood pressure — so it appears that exercise is a key ingredient for kicking these receptors into motion.

The changes were small, Millar notes, and not dire by any means, but they may serve as a way to identify people who may be particularly at risk for high blood pressure later on.

“This helps to provide a mechanism to show that there’s potentially a genetic component. But I think the goal would be that given the high blood pressure response to exercise and given the future risk of cardiovascular disease, this could be an identifier,” he adds.

source:-.inverse