Steve Jackson’s in the midst of a renaissance, it seems. Earlier this year we took a look at Inkle’s Sorcery!, which adapts the 1980s adventure gamebooks of the same name into a modern hybrid of choose-your-own-adventure and RPG—with the help of Inkle’s fantastic writing.

And so imagine my feelings of deja vu as The Warlock of Firetop Mountain crossed my desk—another adaptation of a Steve Jackson adventure gamebook, this one from 1982 and co-authored with Ian Livingstone.

As I said: A renaissance.

In search of Zagor

You begin The Warlock of Firetop Mountain by choosing your character from a stock of four “Allansian Heroes.” Each has different stats and a different quest that’s sent them plunging into the depths of the titular Firetop Mountain. Dekion Strom, for instance, enters Firetop Mountain in search of a locket stolen from him by a crafty goblin named Rotgut. Another character, Alexandra of Blacksand, is paid by a mysterious benefactor named Kith to bring the warlock Zagor a ruby known as the Eye of the Cyclops.

Running the game repeatedly allows you to eventually unlock four more characters, with eight more listed as “Coming Soon!”—all sixteen with his or her (or its, in the case of some monster-characters) own reasons for being in Firetop Mountain.

It’s a small but essential difference between The Warlock of Firetop Mountain andSorcery. The latter, with four books worth of adventures, is a very lengthy and forgiving game with key choices along the way. When you die, you rewind back to the last point and try again.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is a short game with a lot of branches in a short span. It’s mechanically pretty similar to Sorcery—played mostly in text, with long passages (presumably) lifted straight from the original book. Potentially elaborated upon, where necessary. But with a smaller environment and a shorter time-frame, choices are more mundane. Instead of “Do you visit this remote town or this hut in the woods?” you’re more concerned with “Do you take the eastern hallway or the northern?”

It’s a dungeon-crawl, pure and simple, and you should expect to die and die often. Sometimes with absolutely zero warning. The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, like the choose-your-own-adventures of old, is obsessed with killing the player—and unlikeSorcery there’s no take-backs button. On particularly good runs you might opt to burn a Resurrection Stone and continue from the last checkpoint, but you only have a few so you’d better make it worthwhile. Often, the smarter choice is to hop back to the main menu and start over again.

I admit, it can get a bit frustrating at times. Once you’ve learned the patterns of the first dozen or two dozen rooms, re-running them after a death can feel like a chore. Grab the meat, distract the hounds, duck through the door, grab the gold… You start to form a step-by-step guide to Firetop Mountain’s various dangers.

You’ll also notice yourself pushing further into the mountain, though. You skillfully avoid the cave full of spiders your next run. You remember where the goblins hid the Potion of Invisibility. You dodge past the troll. And eventually you find yourself standing outside the ghoulish Domain of the Dead, thinking “I am absolutely not ready for this.”

There’s also a plus side to the game’s more constrained scope, in that it’s enabled the developers at Tin Man Games to invest quite a bit more into the artwork. Sorcery makes do with minimalism—a pawn to represent the player, a hand-drawn map to represent a kingdom. And it’s successful! Sorcery is beautiful in its own gamebook sort-of way.

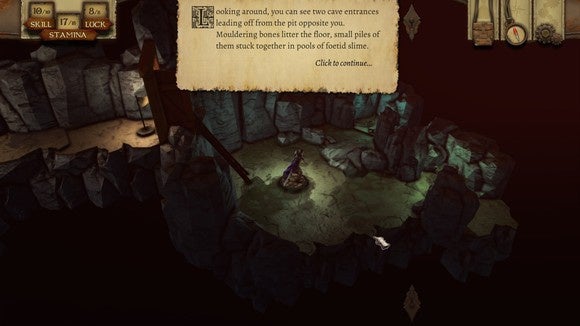

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain goes a step further though and renders the entire book into three dimensions. If you’ve ever played a tabletop RPG and been lucky enough to have your dungeon master build out a miniature set, that’s what Tin Man’s done here. If the text says you enter a cave with an arch to the north, you’ll see the arch to the north. If there’s a pool in the middle of the room filled with some sort of ominous red liquid, then you’ll see the pool. If there’s a cave troll, well, you’re probably dead—but also there’s a cave troll.

It’s absolutely delightful, and even two dozen runs into the game I’m having fun ducking down paths I missed and seeing what’s in store. The best moments are when the hand-drawn art from the original Warlock of Firetop Mountain adventure gamebook pops up in the game, similar to Sorcery, and you can one-to-one compare the old art with the new game’s representation.

The board game feel even extends to your character, rendered as a two-inch tall miniature complete with circular base. To complete the motif, he or she hops around the environment as if controlled by the invisible hand of the player.

And while it’s more of a stylistic touch during the game’s quieter moments, the miniatures double as figurines for combat. Played out on a grid, akin to a real tabletop RPG, the turn-based system has the player and all enemies move or attack simultaneously. It’s surprisingly strategic, though once you master the patterns of the simpler enemies you’ll notice ways to exploit their programming.

Bottom line

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is an excellent adaptation. Like Sorcery, it never really transcends the cheesy sword-and-board adventure-fantasy of the original adventure gamebook it sources from, but that’s not really the point is it? Hell, the archetypal characters and straightforward questing are part of the charm. Tin Man’s lovingly reshaped Steve Jackson’s work into a relaxing and lightweight RPG, perfect to run once or twice in a night and hope this time you avoid all Zagor’s traps and make it to the end.

I don’t know what prompted this rush on Steve Jackson’s work, but I’d take a couple more adaptations—whether by Inkle, by Tin Man, or by someone else. It’s fast becoming one of my favorite niche genres.

source”gsmarena”