The skin is our largest and most visible organ. It protects the body behind an impermeable outer covering but is itself constantly on view. Patients with skin diseases thus have nowhere to hide. They are condemned to suffer twice – once from the condition and secondly from the public reaction to it.

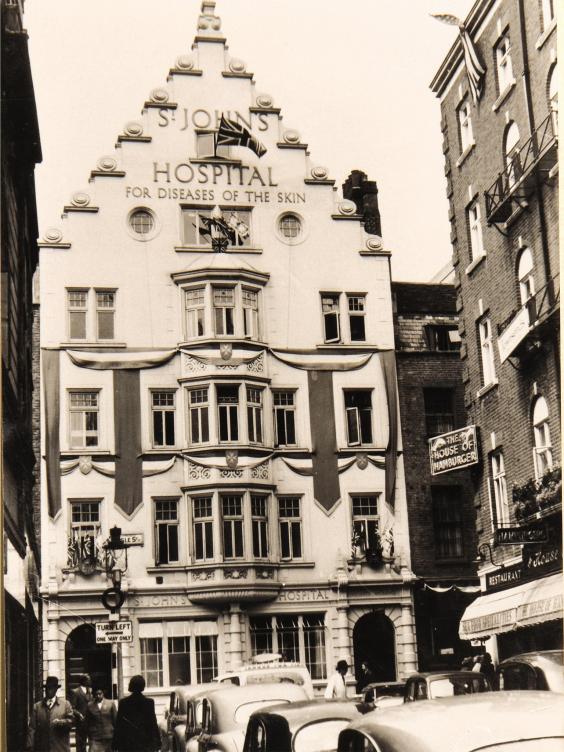

John Milton, who founded St John’s Hospital for Diseases of the Skin in Soho in 1863, understood this. Recognising that his patients had special needs, within two years he had established an evening clinic to cater for the “artisan classes” who risked dismissal from their employment if “it were known they were afflicted with a skin disease”.

St John’s was not the first hospital for skin diseases in the UK but it quickly established itself as the best. The flow of patients that started as a trickle slowly built up till tens of thousands were coming through its doors.

Today, its 36 consultants and 25 clinical nurse specialists, working from their new home within Guy’s Hospital, London, treat patients with the most challenging skin conditions from across the country and the globe.

St John’s founder, John Laws Milton, was a surgeon whose career was cut short by hand eczema. The condition was severe enough to prevent him from operating and that experience appears to have triggered his interest in dermatology.

A maverick figure, Milton rowed with colleagues, was attacked in The Lancet and was involved in several financial scandals. But he also found time to practise medicine.

His recommended treatment for a case of Herpes Gestationis involved “a quart bottle of stout daily, with at least one or two glasses of wine, rum, and milk at night and beef tea ad libitum”.

In another case, he wrote: “She could not bear even zinc ointment, and I therefore directed that she should be covered from head to foot with linen rags dipped in fresh melted suet.”

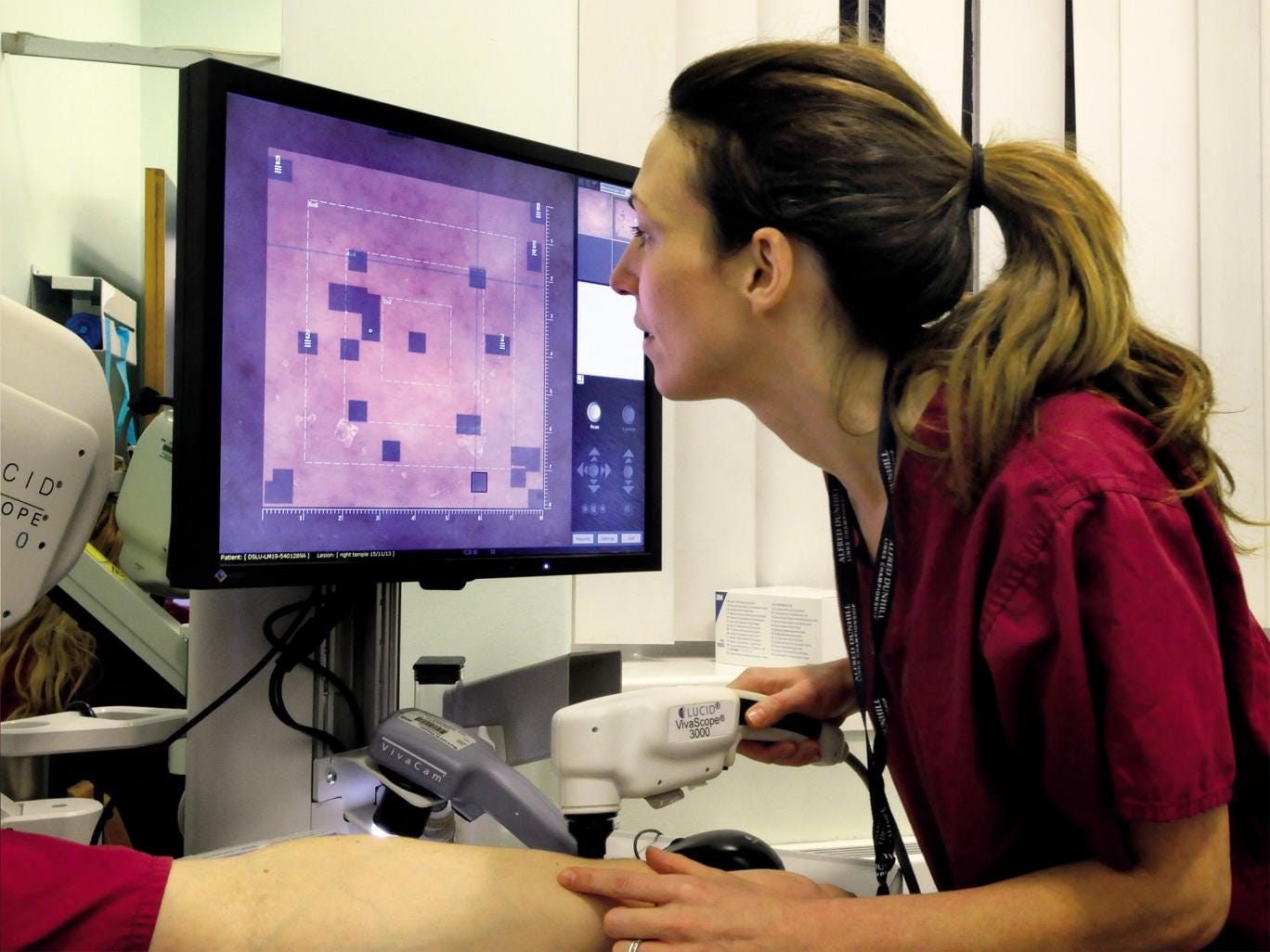

More than a century later, creams and lotions (though not quart bottles of stout) still form a key part of the treatment for many skin conditions. But the type of patients has changed. Forty years ago, skin rashes accounted for nine out of 10. Today, half of all referrals are for suspected skin cancers.

The fastest rising cancer in the UK is melanoma, with more than 12,000 cases a year and 2,000 deaths. Death rates are 70 per cent higher in men although the incidence of the cancer is the same in both sexes. Men tend to wait longer before seeking medical help – with fatal results.

The melanoma service was started at St John’s in the 1990s. It combined plastic surgery and oncology with dermatology to create an early example of the multidisciplinary service that would become standard throughout the NHS over a decade later.

An early challenge was to understand why surgery to remove the lesions successfully halted the disease in some patients while in others it did not. In the 1970s, surgeons made enormous excisions, leaving unsightly scars, in their effort to rid the body of cancer. But the approach failed and today a border of just 2cms of healthy tissue around the lesion is removed.

Professor Sean Whittaker, head of the department, says: “The problem was for those patients who progressed we had no treatment. So the challenge was: could we identify who would progress and do something to help them?”

St John’s answer was to develop sentinel node biopsy, a technique involving the injection of blue dye with a radioactive tracer around the scar which helps surgeons gauge the extent of spread through the lymph system. Surgery is carried out in two stages, 10 days apart, with the second operation designed to “sweep up” after the precise extent of the cancerous tissue has been confirmed in the laboratory after the first operation.

Until recently surgery was the only treatment. But in June 2011, scientists unveiled what has been described as the biggest breakthrough in the treatment of melanoma in 30 years – a twice-a-day pill that halved the death rate among patients with advanced disease. Called vemurafenib, the drug boosted survival rates at six months from 64 per cent to 84 per cent. The improvement was so dramatic that half way through the trial patients who had been randomly assigned to standard chemotherapy were offered the chance to switch to vemurafenib.

The drug was the first “personalised” treatment for melanoma, designed to target cases of the disease carrying the faulty gene, called a BRAF mutation, which account for about half of all cases. It marked a milestone in the transformation of cancer medicines from blunderbuss treatments for everybody to designer drugs tailored to individual cases.

For the future, genes hold the key. Examining the genetic make-up of tumours for abnormalities and the prevalence of the mutations across a population is a major area of research.

Professor Whittaker says: “There are big potential gains on the horizon. We are caring better for our patients and controlling their disease better. We are working to develop a more targeted approach to treatment based on tumour genome sequencing. That promises the next leap forward.”

The first research at St John’s was carried out in 1890 when the treatment for tuberculosis discovered by Robert Koch, who won the Nobel prize in 1905, was trialled in cases of Lupus vulgaris, the most common skin infection associated with the then widespread disease. Lupus vulgaris was a virulent, ulcerating condition that produced a profusion of nodules, most often on the face and neck. Professor Koch’s “fluid”, described as “brown and viscid, the colour of iodine” was delivered direct to the hospital by him for the treatment of what was regarded as the “most disfiguring of all” skin diseases. A committee of three, including John Milton, was established to “enquire into Professor Koch’s discovery and report thereon”.

The Annual Report for 1890 noted: “The investigation with its anxious supervision and hourly observations, has entailed much labour on the whole executive and involved a considerable outlay.” Its outcome is unfortunately not recorded.

The most effective treatment turned out to be the sun. Exposure to sunlight, as well as causing damage to the skin, can ease skin conditions by calming the immune system down and reducing inflammation. This explains why teenagers with acne often find their skin improves in summer with exposure to the sun.

In 1903, Niels Finsen of Denmark was awarded the Nobel prize for producing the world’s first sun lamp to create UV light which he used to treat tuberculosis of the skin. Over the subsequent decades, UV light was used as a therapy for a range of other conditions, including psoriasis.

The evolution of new treatments for psoriasis has transformed the outlook for sufferers – and for St John’s too. The disease affects more than one million people in the UK and one in 50 of the population worldwide. The best-known patient is still fictional hero Philip Marlow, protagonist of Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective. Potter was himself a lifelong sufferer from psoriatic arthritis, and was treated at St Johns. Like Marlow, he was an awkward patient.

The mainstay of treatment for most sufferers is creams and ointments to soothe and moisturise the red, scaly, cracked skin that is the distinguishing feature of the condition and can become sore and painful. Dithranol, a derivative of tar, applied directly to the psoriatic plaques as a paste, was in the past the stand-by treatment but because it could burn normal skin it had to be applied in hospital by trained nurses and required a stay of two to three weeks.

Until a decade ago, there was little more that could be done. Psoriasis – from the Greek word psora meaning itch – was known as the “antidote to the dermatologist’s ego”. Severe cases would spend weeks in hospital and were treated with immunosuppressants such as cyclosporin and methotrexate, to damp down over-active immune systems. But the drugs were only effective in some patients and had serious side effects. Methotrexate was linked with problems of the bone marrow and liver and patients required regular monitoring.

At the turn of the millennium there was a dramatic change. The introduction of the new biologic drugs, custom-designed to target specific parts of the immune system, has transformed the outlook for patients severely affected with psoriasis. At St John’s the first patient was infused with the drug infliximab, a monoclonal antibody, in 2001. Three more biologics have since become available – ustekinumab, the most effective, can be self-injected by the patient just three times a year.

The transformation can be seen in the figures. In 2003-04 there were over 120 in-patient admissions for psoriasis. Three years later there were fewer than 10.

Professor Catherine Smith, consultant dermatologist at St John’s, says: “Patients used to come in and out of hospital. Now we have had an 80 per cent reduction in admissions. These drugs are life-transforming. Almost 70 per cent of patients on treatment are clear or near clear.”

She adds: “They forget they have psoriasis. The treatment is so good they fail to attend their hospital appointments.”

If Dennis Potter was alive today he and his fictional alter ego would have a very different outlook.

The outlook for St John’s has been transformed too. One of the biggest changes in its history has occurred within the last decade – the closure of its in-patient wards. Instead of admitting patients to hospital for six to eight weeks at a time – a frequent occurrence in the past – the vast majority are today managed as out-patients, thanks to advances in drug treatments and phototherapy.

St John’s had two 28-bed wards and they were instantly recognisable by the smell of the lotions and potions (such as coal tar) and the colour of the sheets – not white as elsewhere but dark blue or green. This was necessary to try to disguise the staining that was inevitable when the treatments were applied.

Patients were covered in lotion, wrapped in dressings and given special baths to soothe and treat their inflamed skin. Concoctions based on tar, oils and salicylic acid were used to break down the scales and work on the inflammation. Dithranol, a paste still used today, had to be applied carefully to ensure it was only on the plaques, not on healthy skin where it would burn. It was a laborious process and the paste was slow acting but it could provide remission.

The last in-patient ward was closed in 2005. Today, the Medical Dermatology Day Centre provides the same treatment with one difference – at night the patients go home.

In turn this has transformed the role of the nurse from the traditional position of doctor’s handmaiden to the highly skilled clinical nurse specialists of today who must monitor the treatments, manage side effects and provide care for patients with highly complex conditions and widely varying needs who are living at home.

There has been a big change too in the skin creams and topical treatments used in recent decades. The St John’s pharmacy once featured hundreds of items, including hamamelis (witch hazel) used to produce a soothing ointment, oil of bergamot, the main ingredient of eau de cologne which was used to mask unpleasant smells and hydrargyrum (mercury) used in ointments, now known to be toxic. All these have been superseded today. Some concoctions were specially made up for a single patient, to a recipe their doctor felt would be most appropriate. Small batches of medication with a short shelf life proved expensive and made achieving quality standards challenging. In recent times the British Association of Dermatology has dramatically narrowed the list of approved treatments. Topical steroids and emollients – moisturisers that prevent water loss – are the mainstay today.

There has also been another change. The impact of a disease that affects a patient’s appearance can be severe. Some suffer a catastrophic effect on their ability to function and lead a normal life.

“In the past the psychological impact of skin disease has been the elephant in the room. Nurses didn’t want to inquire too closely how patients were coping because they wouldn’t have known how to help,” says Karina Jackson, a nurse consultant.

Today the need for psychological support has been acknowledged with the appointment of a clinical psychologist in February 2014 to train staff to better understand patients’ needs and to respond to what patients are telling them.

One hundred and fifty years after John Milton established his evening clinic for the artisan classes who lived in fear of losing their jobs, his insight into the prejudice and bigotry suffered by victims of skin disease has been formally recognised.

[“source-